De l’équilibre et de la composition des forces qui agissent sur un point matériel.

1. Un corps nous paroît se mouvoir, lorsqu’il change de situation par rapport à

un système de corps que nous jugeons en repos; mais comme tous les corps, ceux

même qui nous semblent jouir du repos le plus absolu, peuvent être en mouvement;

on imagine un espace sans bornes, immobile et pénétrable à la matière: c’est aux

parties de cet espace réel ou idéal, que nous rapportons par la pensée,

la position des corps, et nous les concevons en mouvement, lorsqu’ils répondent

successivement à divers lieux de l’espace.

1. A body appears to us to be in motion, when it changes its relative situation

with respect to a system of bodies supposed to be at rest ; but as all bodies,

even those which appear in the most perfect repose, may be in motion; a space is

conceived of, without bounds, immoveable, and penetrable by the particles of

matter; and we refer in our minds the position of bodies to the parts of this

real, or ideal space, supposing the bodies to be in motion, when they

correspond, in successive moments, to different parts of this space.

La nature de cette modification singulière, en vertu de laquelle un

corps est transporté d’un lieu dans un autre, est et sera toujours

inconnue ; on l’a désignée sous le nom de force; on ne peut

déterminer que ses effets et les loix de son action. L’effet d’une

force agissante sur un point matériel, est de le mettxe en mouvement,

si rien ne s’y oppose; la direction de la force est la droite qu’elle

tend à lui faire décrire. Il est visible que si deux forces agissent

dans le même sens, elles s’ajoutent l’une à l’autre, et que si elles

agissent en sens contraire, le point ne se meut qu’en vertu de leur

différence. Si leurs directions forment un angle entre elles, il en

résulte une force dont la direction est moyenne entre celles des

forces composantes. Voyons quelle est cette résultante et sa

direction.

The nature of that singular modification, by means of which a body is

transported from one place to another, is now, and always will be, unknown; it

is denoted by the name of Force. We can only ascertain its effects, and the

laws of its action. The effect of a force acting upon a material point, or

particle, is to put it in motion, if no obstacle is opposed; the direction of

the force is the right line which it tends to make the point describe. It is

evident, that if two forces act in the same direction, the resultant is the sum

of the two forces; but if they act in contrary directions, the point is affected

by the difference of the forces. If their directions form an angle with each

other, the force which results will have an intermediate direction between the

two proposed forces. We shall now investigate the quantity and direction of

this resulting force.

Pour cela, considérons deux forces \(x\) et \(y\) agissantes à-la-fois sur

un point matériel \(M\), et formant entre elles un angle droit. Soit

\(z\) leur résultante, et \(\theta\) l’angle qu’elle fait avec la

direction de la force \(x\); les deux forces \(x\) et \(y\) étant données,

l’angle \(\theta\) sera déterminé, ainsi que la résultante \(z\), en sorte

qu’il existe entre les trois quantités \(x\), \(z\) et \(\theta\), une

relation qu’il s’agit de connoître.

For this purpose, let us consider two forces, \(x\) and \(y\), acting at the same

moment upon a material point \(M\), in directions forming a right angle with each

other. Let \(z\) be their resultant, and \(\theta\) the angle which it makes with

the direction of the force \(x\). The two forces \(x\) and \(y\) being given, the

angle \(\theta\) and the quantity \(z\) must have determinate values, so that there

will exist, between the three quantities \(x\), \(z\) and \(\theta\), a relation which

is to be investigated.

Supposons d’abord les forces \(x\) et \(y\) infiniment

petites, et égales aux différentielles \(dx\) et \(dy\); supposons

ensuite que \(x\) devenant successivement \(dx\), \(2dx\), \(3dx\), &c. \(y\)

devienne \(dy\), \(2dy\), \(3dy\), &c., il est clair que l’angle \(\theta\)

sera toujours le même, et que la résultante \(z\) deviendra

successivement \(dz\), \(2dz\), \(3dz\), &c.; ainsi dans les accroissemens

successifs des trois forces \(x\), \(y\) et \(z\), le rapport de \(x\) à \(z\)

sera constant, et pourra être exprimé par une fonction de \(\theta\),

que nous désignerons par \(\varphi\left(\theta\right)\); on aura donc

\(x=z\mathord.\varphi\left(\theta\right)\), équation dans laquelle on

peut changer \(x\) en \(y\), pourvu que l’on y change semblablement

l’angle \(\theta\) dans \(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\), \(\pi\) étant la

demi-circonférence dont le rayon est l’unité.

Suppose in the first place that the two

forces \(x\) and \(y\) are infinitely small, and equal to the

differentials \(dx\), \(dy\). Then suppose that \(x\) becomes successively

\(dx\), \(2\,dx\), \(3\,dx\), &c., and \(y\) becomes \(dy\), \(2\,dy\), \(3\,dy\),

&c., it is evident that the angle \(\theta\) will remain constant, and

the resultant \(z\) will become successively \(dz\), \(2\,dz\), \(3\,dz\),

&c., and in the successive increments of the three forces \(x\), \(y\) and

\(z\), the ratio of \(x\) to \(z\) will be constant, and may be expressed by

a function of \(\theta\), which we shall denote by \(\varphi(\theta)\);

* we shall therefore have \(x = z\mathord{.}\varphi(\theta)\), in

which equation we may change \(x\) into \(y\), provided we also change the

angle \(\theta\) into \(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\),

\(\theta\)

\(\pi\) being the semi-circumference of a circle whose radius is unity.

* Bowditch footnote: (1) A quantity \(z\) is said to be a function of

another quantity \(x\), when it depends on it in any manner. Thus, if

\(z\), \(y\) \(x\)

be variable, \(a\), \(b\), \(c\), &c. constant, and we have either of the

following expressions, \(z=ax+b\), \(z=ax^2+bx+c\); \(z=a^x\), \(z=\sin ax\),

&c. \(z\) will be a function of \(x\); and if the precise form of the

function is known, as in these examples, it is called an explicit

function. If the form is not known, but must be found by some

algebraical process, it is called an implicit function.

Maintenant, on peut considérer la force \(x\) comme la résultante

de deux forces \(x’\) et \(x''\) dont la première \(x'\) est dirigée suivant la

résultante \(z\), et dont la seconde \(x''\) est perpendiculaire à cette résultante.

Now we may consider the force \(x\) as the resultant of two forces \(x'\)

and \(x''\), of which the first \(x'\) is directed along the resultant

\(z\), and the second \(x''\) is perpendicular to it. †

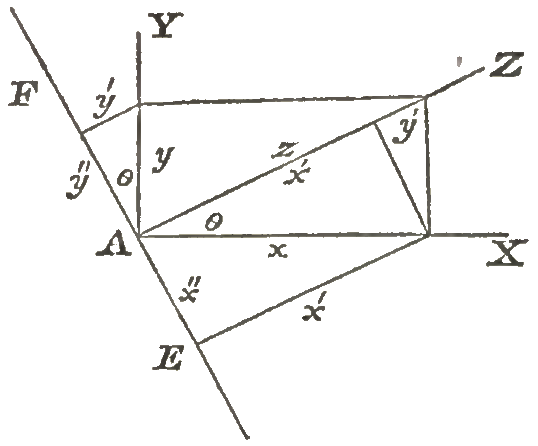

† Bowditch footnote: (2) For illustration, suppose the forces \(x\) and \(y\) to act at the

point \(A\), in the directions \(A\,X\), \(A\,Y\), respectively, and that

the resultant \(z\) is in the direction \(A\,Z\), forming with \(A\,X\),

\(A\,Y\), the angles \(Z\,A\,X=\theta\), \(Z\,A\,Y=\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\).

Then as above, we have \(x=z\mathord{.}\varphi(\theta)\),

\(y=z\,\varphi\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right)\). Draw \(E\,A\,F\)

perpendicular to \(A\,Z\), and suppose the force \(x\) in the direction

\(A\,X\) to be resolved into two forces, \(x'\), \(x''\) in the directions

\(A\,Z\), \(A\,E\), respectively, so that the angle \(Z\,A\,X=\theta\), and

\(X\,A\,E = \frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\). Then, in the same manner in which

the above values of \(x\), \(y\), are obtained from \(z\), we may get \(x'=

x.\varphi\left(\theta\right)\);

\(x''=x.\varphi\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right)\). If in these we

substitute the values \(\varphi\left(\theta\right)=\frac{x}{z}\);

\(\varphi\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right) = \frac{y}{z}\), deduced from

the above equations, we obtain \(x'= \frac{x^2}{z}\);

\(x''=\frac{xy}{x}\). In like manner, if the force \(y\), in the

direction \(A\,Y\), be resolved into the two forces \(y'\), \(y''\), in the

directions \(A\,Z\), \(A\,F\), making the angle

\(Y\,A\,Z=\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\), \(Y\,A\,F=0\), we shall have

\(y'=y.\varphi\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right)\);

\(y''=y.\varphi\left(\theta\right)\); which, by substituting the above

values of \(\varphi\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right)\),

\(\varphi\left(\theta\right)\) become \(y'=\frac{y^2}{z}\),

\(y''=\frac{xy}{z}\), as above.

La force \(x\) qui résulte de ces deux nouvelles forces, formant l’angle \(\theta\)

avec la force \(x'\), et l’angle \(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\) avec la force \(x''\), on

aura \[x'=x\mathord.\varphi\left(\theta\right)=\frac{x^2}{z};\quad

x''=x\mathord.\varphi\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right) = \frac{xy}{z};\] on peut

donc substituer ces deux forces, à la force \(x\). On peut substituer

pareillement à la force \(y\), deux nouvelles forces \(y'\) et \(y''\) dont la

première est égale à \(\frac{y^2}{z}\) et dirigée suivant \(z\), et dont la seconde

est égale à \(\frac{xy}{z}\), et perpendiculaire à \(z\); on aura ainsi, au lieu des

deux forces \(x\) et \(y\), les quatre suivantes: \[\frac{x^2}{z}, \frac{y^2}{z},

\frac{xy}{z}, \frac{xy}{z};\] les deux dernières agissant en sens contraire, se

détruisent; les deux premières agissant dans le même sens, s’ajoutent et forment

la résultante \(z\); on aura donc \[x^2+y^2=z^2;\] d’où il suit que la résultante

des deux forces \(x\) et \(y\) est représentée pour la quantité, par la diagonale du

rectangle dont les côtés représentent ces forces.

The force \(x\), which results from these two new forces, forms the

angle \(\theta\) with the force \(x'\), and the angle

\(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\) with the force \(x''\); we shall therefore have

\[x'=x\,\varphi\left(\theta\right)=\frac{x^2}{z};\quad

x''=x\,\varphi\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\theta\right) = \frac{xy}{z};\] and we

may substitute these two forces instead of the force \(x\). We may

likewise substitute for the force \(y\) two new forces, \(y'\) and \(y''\),

of which the first is equal to \(\frac{y^2}{z}\) in the direction \(z\),

and the second equal to \(\frac{xy}{z}\) perpendicular to \(z\); we shall

thus have, instead of the two forces \(x\) and \(y\), the four following:

\[\frac{x^2}{z}, \frac{y^2}{z}, \frac{xy}{z}, \frac{xy}{z};\] the two

last, acting in contrary directions, destroy each other; * the two

first, acting in the same direction, are to be added together, and

produce the resultant \(z\); we shall therefore have †

\[x^2+y^2=z^2;\]

whence it follows, that the resultant of the two forces \(x\) and \(y\) is

represented in magnitude, by the diagonal of the rectangle whose sides

represent those forces.

* Bowditch footnote: (3) For, by the preceding note, the force \(x''=\frac{xy}{z}\), is in the

direction \(A\,E\), and the force \(y''=\frac{xy}{z}\), is in the opposite

direction \(A\,F\), and as they are equal they must destroy each other.

† Bowditch footnote: (4) The sum of the two forces \(x'=\frac{x^2}{z}\), \(y'=\frac{y^2}{z}\) in the

direction \(A\,Z\), being put equal to the resultant \(z\), gives

\(\frac{x^2}{z}+\frac{y^2}{z}=z\), which multiplied by z becomes \(x^2+y^2=z^2\).

Let us now determine the angle \(\theta\). If we increase the force \(x\) by the

differential \(dx\), without varying the force \(y\), that angle will be diminished

by the infinitely small quantity \(d\theta\); * now we may conceive the force

\(dx\) to be resolved into two other forces, the one \(dx'\) in the direction \(z\),

and the other \(dx''\) perpendicular to \(z\); the point \(M\) will then be acted upon

by the two forces \(z+dx'\) and \(dx''\), perpendicular to each other, and the

resultant of these two forces, which we shall call \(z'\) will make with \(dx''\)

the angle \(\frac{}{}-d\theta\); † we shall thus have, by what precedes,

\[dx''=z'\mathord.\varphi\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-d\theta\right);\] consequently the

function \(\varphi\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-d\theta\right)\) is infinitely small, and of

the form \(-kd\theta\), \(k\) being a constant quantity, independent of the angle

\(\theta\); ‡ we shall therefore have